This article first appeared on the 18/11/2015 on Times Higher Education

Given the impending doom of the spending review, academics are

becoming more mindful of what is expected of them by their political

paymasters. A recurring piece of rhetoric around universities is that

research should have “impact”. But what does impact really mean, is it a

valid metric and should you be chasing it?

Impact is the new translation

Impact, defined on the Research Councils UK web pages as “positive

impact in our society and economy…through knowledge exchange, new

products…and so on”, is the potential of the research to make changes in

the real world outside the university gates. It is different from

“high-impact” papers – another different kind of evil, another gripe,

another blog. Making research quantifiable and beneficial is a

noble-sounding ideal and much/some/a little (delete as applicable) of

the research performed has a clear and quantifiable impact – eventually.

Lost in translation

I have two concerns with using impact as a metric. First, I believe

it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict which new avenues of

basic research will have the most impact. Second, I believe too great a

focus on impact can harm innovation, leading to shorter-term thinking

and a narrowing of the horizon. A clinical trial of a drug is clearly

closer to impact than understanding the crystal structure of a molecule,

but the drug may have been designed based on crystal structures

generated decades ago. If we cut the root of research today, we won’t be

able to deliver the fruit of clinical trials tomorrow. Think of the

laser, green fluorescent protein, the structure of DNA and monoclonal

antibodies. All of these were discovered and developed with minimal

consideration of impact or their possible industrial applications but

now underpin vast industries.

Blue-sky impact

Ideally, we would get rid of impact as a metric altogether.

University research labs should be viewed as feeder blue-sky labs. Owing

to financial pressures, many companies no longer sustain pure-science

basic-research facilities. Universities can fill this gap, playing to

the strengths of both partners – academics have time to develop random

thoughts; industry has the cash and the experience to see things to

market. Yes, that does mean that publicly funded research supports

private industry, but since we are told that one of our major functions

should be to spark economic growth, this is a good thing.

Past performance equals future impact (maybe)

Sadly, in this age of metrics for everything, vaguely asserting that

research has downstream benefits is probably insufficient. So how should

impact be measured? I would argue that at an individual level, past

performance is an ineffective metric, biasing towards more established

groups, when historically disruptive innovation comes from outsiders,

new starters and people with less to lose. However, assessing the impact

of previous work at an institutional level is effective. Although

time-consuming (and costly), the impact studies in the 2014 research

excellence framework (REF) did clearly show how universities add value.

Institutions with a history of impactful work over a longer time period

are, I believe, more likely to deliver it again in the future. In

academia, the larger institutions have the reputation to pull in the

best thinkers, the resources to support them and the infrastructure to

enable researchers to research.

Game it

Sadly, my saying that impact is an inappropriate metric is not going to change the system (although I am happy for Jo Johnson,

the minister for universities and science, to prove me wrong). We are

stuck with impact and therefore need to play the game by writing

awe-inspiring impact statements. In these times of slender research

budgets, grants have been won or lost on the perceived quality of the

impact. Read the advice

on the RCUK pages and get tips from academic mentors. But to take it a

step further, be inventive. This is the one part of the grant where you

can just make stuff up* – it is hard enough quantifying impact

objectively after the work is done, it is impossible to quantify impact

before the work is done. So say that your research can cure cancer,

cancel Third World debt and fix the ozone layer, because you know what,

some of it will.

* This is for comic effect to emphasise a point – I would never

make anything up. My work WILL cure the common cold (in the space of a

three-year project).

Some sporadic insights into academia.

Science is Fascinating.

Scientists are slightly peculiar.

Here are the views of one of them. Buy My Book

Science is Fascinating.

Scientists are slightly peculiar.

Here are the views of one of them. Buy My Book

Monday, 14 December 2015

Academic failure: four more ways to deal with it

I had intended to focus on some of the many core skills needed in an

academic career: selling your science, the importance of brand and how

to collaborate. But I got derailed.

It turns out you can come up with all the carefully phrased advice, witty but apposite anecdotes and strategies for coping with failure. You can think outside the box and look on the bright side, but occasionally the wheels come off.

Twenty-four hours ago, I was sitting at my desk working on the third draft of a grant proposal that I have been tortuously pulling together for many months when I had an unshakeable feeling that “this is unfundable garbage; what am I doing here, my career is in tatters”. I slowly sank into despair.*

That I had recently written upbeat pieces about failure and building resilience, combined with my inability to listen to my own advice, only added to my frustration.

You may wonder why I am sharing this in a blog purportedly about academic career development. Mainly, it is to (re)emphasise a key point: we all struggle with the ups and downs of academic life, and anyone who says they don’t is lying, not trying hard enough...or emeritus.

It is also to emphasise that every glowing opportunity is accompanied by a kick in the bum. Failure is rife and disappointment common.

I also wanted to share what worked for me in order to compress my time in the doldrums and accelerate a return to productivity. The route back up involved support, distraction and time.

Support

There are times when you need to draw on your network of friends, family and colleagues to hold your hand (literally and figuratively), to send you friendly emojis and reassure you that your idea is OK (or at least has salvageable parts). But make sure you are available to return the favour when the positions are reversed.

Step outside the moment

For me, exercise resets the balance. For you it might be music, drawing, playing Grand Theft Auto or cooking. I said this in my last blog but will stress it again, if only for my own benefit: if one aspect of the job gets too much, do something else. Defrost a -80°C freezer, order lab consumables or clean the incubators. Find your stress relief valve and make sure it is accessible at work.

In an attempt to manage myself better, I have now got running kit in a drawer in my office, to be deployed in emergency.

Time

The simplest factor is time: time away from the desk, time to reflect on the good bits and time to refocus.

Lessons learned

The moment passes, there will be bits you can salvage and, if not, you have learned what doesn’t work.

My problem is fear of failure, but you can’t win the lottery unless you buy a ticket, and you can’t get a grant unless you submit a proposal. I’d like to hope that having reflected on the stresses of failing (again) I won’t get into the same state (again). However, I am sure I will – but maybe next time I will be self-aware enough to break out the running shoes earlier.

* Note to my funders and employers: this was unfounded. My grant proposal is amazing. In fact you should fund it without even reading it.

This first appeared on 13/10/2015 on the Times Higher Education

It turns out you can come up with all the carefully phrased advice, witty but apposite anecdotes and strategies for coping with failure. You can think outside the box and look on the bright side, but occasionally the wheels come off.

Twenty-four hours ago, I was sitting at my desk working on the third draft of a grant proposal that I have been tortuously pulling together for many months when I had an unshakeable feeling that “this is unfundable garbage; what am I doing here, my career is in tatters”. I slowly sank into despair.*

That I had recently written upbeat pieces about failure and building resilience, combined with my inability to listen to my own advice, only added to my frustration.

You may wonder why I am sharing this in a blog purportedly about academic career development. Mainly, it is to (re)emphasise a key point: we all struggle with the ups and downs of academic life, and anyone who says they don’t is lying, not trying hard enough...or emeritus.

It is also to emphasise that every glowing opportunity is accompanied by a kick in the bum. Failure is rife and disappointment common.

I also wanted to share what worked for me in order to compress my time in the doldrums and accelerate a return to productivity. The route back up involved support, distraction and time.

Support

There are times when you need to draw on your network of friends, family and colleagues to hold your hand (literally and figuratively), to send you friendly emojis and reassure you that your idea is OK (or at least has salvageable parts). But make sure you are available to return the favour when the positions are reversed.

Step outside the moment

For me, exercise resets the balance. For you it might be music, drawing, playing Grand Theft Auto or cooking. I said this in my last blog but will stress it again, if only for my own benefit: if one aspect of the job gets too much, do something else. Defrost a -80°C freezer, order lab consumables or clean the incubators. Find your stress relief valve and make sure it is accessible at work.

In an attempt to manage myself better, I have now got running kit in a drawer in my office, to be deployed in emergency.

Time

The simplest factor is time: time away from the desk, time to reflect on the good bits and time to refocus.

Lessons learned

The moment passes, there will be bits you can salvage and, if not, you have learned what doesn’t work.

My problem is fear of failure, but you can’t win the lottery unless you buy a ticket, and you can’t get a grant unless you submit a proposal. I’d like to hope that having reflected on the stresses of failing (again) I won’t get into the same state (again). However, I am sure I will – but maybe next time I will be self-aware enough to break out the running shoes earlier.

* Note to my funders and employers: this was unfounded. My grant proposal is amazing. In fact you should fund it without even reading it.

This first appeared on 13/10/2015 on the Times Higher Education

Failure is an option: six ways to deal with it

Are you ready to fail, because as an academic you will, repeatedly.

We all do. Failure is part and parcel of academia. The two repeat offenders are grants and papers and, of the two, grant failure feels more brutal (to me at least). If you are like me, you will take each failure really badly, and it will ruin numerous evenings and weekends (and on one occasion, a child’s birthday party).

To avoid this, it is important to develop coping strategies, a lot of them grounded in approaches to build mental resilience. Here are six that might help:

Mindset

I cannot recommend strongly enough the brilliant book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck, Lewis and Virginia Eaton professor of psychology at Stanford University. In brief, don’t take failure as a blow to your self-esteem; look at it as a learning opportunity. There may be a good reason why the grant or paper failed. Don’t think: “stupid reviewers, why don’t they understand me”; do think: “how can I write that better so it makes sense to even the most stupid reviewer”.

There are other opportunities

Failure is very rarely the end of the line. Grants are on a rolling cycle and many applications only get accepted on the 2nd or 3rd submission. That journal you were striving for is probably not as great as you thought, and there are more journals than ever, so your paper will find a home. Convince yourself that impact factor is an artificial construct. Successful academics are determined (bloody minded). Think how many job applications and interviews you had in order to get here and apply that same spirit now you have the job.

It’s nothing personal

Unless you ran off with the reviewer’s partner, killed their grant or ran over their dog, the critique of your work is about your work and not about you. Taking it to heart, memorising key lines and writing “you are an idiot” in red pen on the comments is satisfying but doesn’t get the grant funded. Look at it from the reviewer’s point of view: they have limited time to make decisions on a large number of grants from a range of subjects. Bear in mind that we are all called to be reviewers and through negligence, weakness or our own deliberate fault we sometimes get it wrong.

You’re not unique

Look up the success rate of your grant scheme, then take the inverse – that is how many people you are in company with. More applicants fail than succeed. Find them, commiserate and move on.

What would Alan Sugar say?

Remember, you are selling, they are buying. You have to make sure the fit is right and the sales pitch correct.

Learn from what goes well

While failure may seem bad, success has its downsides too. You’ve actually got to do the work that sounded so good on paper. You’ve then got to think of bigger and better new ideas. At least if you are unsuccessful, you can recycle the good parts of the application.

Remember, academia is just a job. It may take up all your time, intellectual capacity and emotional energy, but it is still just a job.

Take a step back, do something unrelated – garden, run, swim, paint, sing. Apologise to the child whose birthday you ruined, and then on Monday morning pick up your pen and start again.

This first appeared 19/09/2015 on the Times Higher Education

We all do. Failure is part and parcel of academia. The two repeat offenders are grants and papers and, of the two, grant failure feels more brutal (to me at least). If you are like me, you will take each failure really badly, and it will ruin numerous evenings and weekends (and on one occasion, a child’s birthday party).

To avoid this, it is important to develop coping strategies, a lot of them grounded in approaches to build mental resilience. Here are six that might help:

Mindset

I cannot recommend strongly enough the brilliant book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck, Lewis and Virginia Eaton professor of psychology at Stanford University. In brief, don’t take failure as a blow to your self-esteem; look at it as a learning opportunity. There may be a good reason why the grant or paper failed. Don’t think: “stupid reviewers, why don’t they understand me”; do think: “how can I write that better so it makes sense to even the most stupid reviewer”.

There are other opportunities

Failure is very rarely the end of the line. Grants are on a rolling cycle and many applications only get accepted on the 2nd or 3rd submission. That journal you were striving for is probably not as great as you thought, and there are more journals than ever, so your paper will find a home. Convince yourself that impact factor is an artificial construct. Successful academics are determined (bloody minded). Think how many job applications and interviews you had in order to get here and apply that same spirit now you have the job.

It’s nothing personal

Unless you ran off with the reviewer’s partner, killed their grant or ran over their dog, the critique of your work is about your work and not about you. Taking it to heart, memorising key lines and writing “you are an idiot” in red pen on the comments is satisfying but doesn’t get the grant funded. Look at it from the reviewer’s point of view: they have limited time to make decisions on a large number of grants from a range of subjects. Bear in mind that we are all called to be reviewers and through negligence, weakness or our own deliberate fault we sometimes get it wrong.

You’re not unique

Look up the success rate of your grant scheme, then take the inverse – that is how many people you are in company with. More applicants fail than succeed. Find them, commiserate and move on.

What would Alan Sugar say?

Remember, you are selling, they are buying. You have to make sure the fit is right and the sales pitch correct.

Learn from what goes well

While failure may seem bad, success has its downsides too. You’ve actually got to do the work that sounded so good on paper. You’ve then got to think of bigger and better new ideas. At least if you are unsuccessful, you can recycle the good parts of the application.

Remember, academia is just a job. It may take up all your time, intellectual capacity and emotional energy, but it is still just a job.

Take a step back, do something unrelated – garden, run, swim, paint, sing. Apologise to the child whose birthday you ruined, and then on Monday morning pick up your pen and start again.

This first appeared 19/09/2015 on the Times Higher Education

Friday, 13 November 2015

Intramuscular Immunisation with Chlamydial Proteins Induces Chlamydia trachomatis Specific Ocular Antibodies.

Pub Quiz time: What obligate intracellular pathogen infects the eye and is a major cause of blindness? (As you may guess I don’t

get to many pub quizzes!). The answer is Chlamydia, with a bonus point for the

full name Chlamydia trachomatis. And yes it is the same type of bacteria that

causes the sexually transmitted infection, chlamydia. In fact there are 12

strains of chlamydia, a-c cause the eye disease, d-k cause the sexually

transmitted infection and L causes an invasive sexually transmitted infection. Interestingly*,

the way chlamydia infection causes disease in either the eye or the genital

tract is the same. The immune response is too aggressive, leading to damage of

the surrounding tissue, which has bad consequences in sensitive organs such as

the eyes or ovaries.

Chlamydia of the eye

Chlamydia infections causes the disease trachoma, which

leads to 4.9 million cases of blindness annually inlower and middle income

countries. For more information visit the international trachoma initiative. It

is described as a disease of poverty because it is most prevalent in locations

with poor access to clean water. It is also categorised as a neglected tropical

disease by WHO, with the aim that this will encourage a greater research

effort. For example if companies work on these diseases they are eligible for

FDA priority review vouchers which allows them to accelerate licensure of other

drugs. The current treatment regime is to use antibiotics -

Azithromycin . This is cheap and effective especially since Pfizer donate free Zithromax®.

However with antibiotic treatment of bacterial infections there is always a

risk that the bacteria become resistant to the drugs, which then become less

effective. So it is prudent to look for alternative.

Eye protection

In our recently published study, we were investigating new vaccines. Because it is a disease of the eye,

we trying to improve the protective immune response in the eye. We developed a

new technique for measuring antibody (the super molecules that are able to

recognise bacteria by their shape). We observed that some of the new vaccines

we tested led to the measurable antibody in the eye, which might protect

against infection. This work has now lead (in collaboration with our Danish

partners from SSI, Copenhagen, into a clinical trial in people, that will test

vaccines for safety, but also measure antibody in the eye. This work was made

possible by support from the EU as part of a multi centre consortium called

Aditec.

* Interestingly is a horrible science writing device – often

gets irate reviewer’s commenting about the reader getting to decide what is

interesting, but the good thing about writing an unreviewed blog is that I can

say what I like.

PS thanks to Alex (Badamchi) for proofing this and filling in the details

PS thanks to Alex (Badamchi) for proofing this and filling in the details

Thursday, 24 September 2015

Going global!

If you have any personal contact with me - Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin,

Email, Carrier Pigeon etc you are probably bored of me plugging my blog in The Times Higher Education supplement! But if you are on this site and have come not because I have cajoled you into it, you may be wondering why it has gone a bit quiet. The main answer is the summer holiday, but I have been working on pieces for other outlets, oh did I mention this one for the Times Higher Education

Tuesday, 4 August 2015

Buy one get one free?

PHiD-CV induces anti-Protein D antibodies but does not augment pulmonary clearance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in mice

Synflorix – a highly effective vaccine for S. pneumoniae

In our recent study (Siggins et al) published in the journal Vaccine we

were looking at a commercially available vaccine called Synflorix (technical

name PHiD-CV). This is a vaccine made by GSK against the bacteria called Streptococcus

pneumoniae. This bacteria causes pneumonia (unsurprisingly – the name is a bit

of a give away) but more seriously it causes a range of conditions called

invasive pneumococcal disease where the bacteria crosses from the airways into

the rest of the body leading to diseases like meningitis and sepsis. One of the

problems with preventing Streptococcus pneumoniae infections (or Strep pneumo)

is that there are many different forms of the bug and so a vaccine needs to

protect you against as many of them as possible. Synflorix is highly effective at providing protection

against 10 of the Strep pnuemo strains.

Sweet on the outside, deadly in the middle

The aim of our study was slightly different. Bacteria are a

bit like the blue liquorice allsorts, with a bobbly sugar coat hiding a

disgusting middle. Our immune system only recognises the outside part of the

bacteria which is made up of complex sugars (polysaccharides). These molecules,

unlike proteins, are not particularly well recognised by the immune system

(poorly immunogenic). One trick to improve the immunogenicity of the sugars is

called conjugation. This is where the sugars are chemically bound to proteins,

which are better recognised by the immune system, and in a biological sleight

of hand you the white blood cells into improving the response. A number of

different bacterially derived proteins are used as the carrier protein to boost

the immune response including ones from Tetanus and Diphtheria. In the current

study we were looking at the effect of a protein derived from non-typeable H.

influenzae (NTHi) called protein D. The aim was to see whether the protein D part of the Synflorix vaccine could give broad cross protection against NTHi in addition to Strep pnuemo.

NTHi is the new HiB

I guess you are wondering why we would want protection

against NTHi, or probably more honestly, what on earth is NTHi? Haemophilus

influenzae (the Hi in NTHi) is a bug we all carry in our throats and noses, which

sometimes causes illness and occasionally causes meningitis. However,

Haemophilus is divided into different types based on its sugar coat. It is the

B type or HiB that is highly invasive and there is a vaccine for this, included

in the UK infant schedule at 2, 3 and 4 months, which has significantly reduced

the incidence of meningitis. Haemophilus are grouped (or Typed) by the sugar

they are covered in, some don’t have a sugar coat and are so non-typeable (the

NT in NTHi). Whilst the non-coated strains rarely cause invasive/ meningitis

disease, they do lead to a significant amount of community acquired pneumonia.

NTHi lung infections are particularly common in patients who are long term

smokers and have the ongoing lung damage from smoking (COPD). There is therefore

an economic argument for reducing the burden of this disease, especially if it

can be achieved as a side effect of a vaccine that is designed to prevent a

different bacterial pathogen, which brings us back to the current study.

No cross protection

It is very complicated to perform the types of study needed

to define whether Synflorix gives cross protection against NTHi in patients.

This is because the majority of NTHi infections cause pneumonia and the

causative agent of pneumonia is rarely defined when patients go to their GPs.

To get around this we developed a mouse model of NTHi lung infection. When

infected with NTHi mice got sick and we were able to detect the bacteria in the

lungs and airways. This gave us a model to test the vaccine in. Mice were given

Synflorix (the vaccine we wanted to test) or another pneumonia vaccine called

Prevenar (which has the same Streptococcus components, but doesn’t use the NTHi

protein). The vaccine was good at inducing an immune response and we were able

to measure antibodies specific to NTHi Protein D. So far so good, unfortunately

when we infected the vaccinated mice with NTHi, there was no difference between

the vaccinated ones and the control/ unvaccinated mice, either in how sick they

got or how much bacteria was in their lungs. From this we drew the conclusion

that sadly in our hands and in our system, Synflorix does not give the extra

protection against the second organism – NTHi. This doesn’t mean it isn’t a

highly effective vaccine against S. pneumoniae, which it is.

The no’s have it.

This study was a piece of what we call negative data. Ben

Goldacre (@Bengoldacre) goes into this much more eloquently than me, but

negative data is really important. It may not be as exciting as finding

something new and positive, but by publishing negative, you 1) stop someone

else doing the same thing which 2) reduces the cost of repeated research, 3)

reduces the numbers of people and animals that get used in the process. This

work was kindly supported by the charity Sparks and whilst in this case did not

change clinical practice, it is an important piece of basic research. It may

inform policy about which vaccine to use and therefore free up money to be

spent elsewhere. We are really grateful to the people who raise money for the

charity and encourage you all to get on your running shoes and raise more money

so we can perform the research to find out whether vaccines do (or just as

importantly do not) work.

Friday, 17 July 2015

The 4 elements of Academia

Professor Beardyman

Just to show I am down with the youth, I am going to compare

academia to hip hop.

As you all know, there are 4 fundamental elements of Hip-Hop. You knew that

didn’t you? You didn't? Oh allow me to educate you – they are:

|

| Beardyman: Though the beard may be a bit oversold |

1. Bboying

2. MCing

3. Graffiti

4. DJing. Obviously.

Why am I showing off my Vanilla Ice like knowledge of the

patois of modern culture? Well there are 4 elements to academia, publishing,

grant writing, teaching and admin. In my quest to inform the great unwashed

(yes that’s you, the one not really paying attention in the back) about what

academics do, this week’s tortured musing is going to give an overview of why

we think these elements matter. Though you will be pleased to know I am not

going to stretch my torturous analogy to linking say Grant writing to B-boying

– mainly because I don’t know what Bboying is!

Zen and the art of university maintenance

There are 3 ways of viewing the elements

Idealistic: Universities are dreaming spired bastions of

learning and higher education where we educate young minds, push back the

boundaries of knowledge and enrich the greater good by applying Kantean

dialectics to the routes of the romantic poem. In this worldview teaching is

central, admin is giving back to the university, paper writing a joy and grants

a dirty word as there should be an inherent understanding of the intrinsic good

our esteemed institutions do.

Fatalistic: The economy is fucked, George Osborne is busily

grinding the last traces of state funded endeavour into a dry dust of free

market neo-con fury. In this less than enlightened time, we have to pay our way

and our work has to have IMPACT (if there was an option to make the word flash

and somehow sear itself into your skin, that would be the font I should use, but a whole other blog is needed to talk about IMPACT). Our work is publicly funded from hard working

honest tax payers' money and we should never be allowed to forget it. The

university is a business and every action should be to support the mission

statement and bring money into the university.

A third way: Like the force, there needs to be balance in the univers(ity).

The money that pays for our salaries does come from somewhere and most of

it comes from the taxpayer. In return I need to do something more productive

than watch Beardyman videos on YouTube (though the kitchen diaries is awesome). Academics do need

to contribute to the running of the place and the education of the students.

But at the same time we should be in a position to carry on researching the relative

importance of early-latin swear stones (if we wish).

The academic transfer market (my one paragraph of soapbox ranting)

These different approaches have an impact on university

life. As with all educational institutions in the UK, universities are ranked

and what does ranking bring…Prizes (or substantial funding from the government

in the form of QR and QT grants from the Department for Business, Innovation

& Skills, but prizes is more catchy). They are ranked on a number of

different criteria, but the two big ones are the REF (a quinquennial exercise

evaluating research output and IMPACT) and the QA (which evaluates teaching). These

evaluations are based on individuals, which generates a transfer market in academics,

with the superstar professors moving between the big universities demanding

more space, more salary, more acolytes and flunkies to peel them raw grapes. This

can have a number of negative repercussions: focussing resources on a small handful

of individuals, damaging departmental cohesion, depleting the pension pot (which

was final salary based) and putting academic career development at a lower

priority – why train people when you can just buy someone in. The other concern

is just because they are big hitters doesn’t mean they are team players and the

perceived benefit of what they bring may be offset by the friction and resentment

they cause. To crunch metaphors, we should aspire to have more Stephen Gerrards (who played for one club his whole career, possibly to the

detriment of the amount of medals he won), people who grew up in one

institution are to my mind, more likely to be loyal to that institution, understand

the culture of the institution and are more inclined to contribute in the small

ways necessary to keep it running. Then again, we can all get a bit inward looking and fresh perspective always helps.

Nick Clegg and the new student generation.

Crikey, got slightly off topic there. Must. Focus. 12 months

ago I would have said that successful

grant writers will inherit the ivory towers. They were perceived to bring in cold hard

cash that pays for the buildings, the electricity, the salaries of the people

who work in the mystery blue box (and as a sideline get a small bit of

money to do research). However, times have changed, and the quants who run the

institutions have realised that students = money: £9,000 x as many people you

can squeeze into a lecture theatre per year. This has the beginnings of a major

revolution in universities. Firstly (and don’t tell them) this gives the

students real power as consumers, if the teaching is not up to scratch they can

head to the twitterbookapp thingy and troll the course – luckily most of them

are too busy being students to realise this empowerment. Secondly, those who

teach and particularly those who teach well, suddenly have become more

valuable. With the increased focus on teaching, it is possible that the

superstar teachers will now also be commoditised and traded between the

colleges. I suspect we are a way off Panini doing a sticker album of high

flying academics, buy maybe academic top trumps is not too inconceivable!

Imagine the fun - oh no I can’t believe you beat my Nobel Prize winner with

your senior administrator.

Not so Deep Conclusion

Academics need to deliver a range of diverse

functions within the space of the working day (like most jobs). I would argue that the breadth

of skills required is unique, ranging from preparing sales pitches to writing technical

literature to teaching to management. Then again I have no experience of any

other job, except stacking shelves in a refrigerated warehouse, so have little

to compare it against. There are some people who excel in a single area and are

prized by the institutions, but the rest of us have to muddle by with a mix of

all aspects.

Tuesday, 30 June 2015

Break the bug, spare the child. The partial attenuation of Small Hydrophobic (SH) gene deleted RSV is associated with elevated IL-1β responses.

|

| Maurice Hilleman Hero of the 20th Century |

However, we are now using more targeted approaches to attenuate

viruses and bacteria. This is based on our improved understanding about how

pathogens are able to infect people. For example what do they look for on the

surface of cells to invade them, how do they coerce the machinery of the cell

to make copies of themselves rather than more cells and critically how do they

hide from the immune response. All human viruses have evolved ways of escaping

the immune response (immune evasion), viruses that are not able to escape our

immune response are not able to infect us – that’s why for example we don’t get

myxamatosis from rabbits. In our recently published study in the Journal of Virology, we discovered a new

immune evasion function for a gene in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV is

a really important disease in children, causing 160,000 deaths worldwide and

hospitalising 1% of all children under 1 in the UK (including my son).

The gene we were interested in is called SH (or small hydrophobic

gene – sadly whilst drosophila geneticists get to call genes things like sonic the hedgehog and LUSH, we get names based on the structure or function, or

sometimes just the order they were found). It is believed to make a small

hydrophobic protein (can you see what we did there!) which folds up to make a

pore or tube like structure. Based on other studies using similar proteins from

other viruses, we hypothesized that this protein would actually alert the

immune system, so we were surprised to find that infection with RSV lacking SH

(RSV ΔSH) led to MORE of specific type of signal rather than less. We then saw

that if this signal was blocked, the virus – which previously grew less well in

lungs, grew to the same level as unchanged virus. We think this might be

important both in our understanding about viral biology and possibly in

developing strategies to make targeted vaccines. We were supported in this work

by two grant programs from the EU, Aditec and Biovacsafe, which has enabled a lot of the work in the lab to be

performed.

Monday, 22 June 2015

What's the difference between a Jelly fish and a vaccine?

A Comparison of Red Fluorescent Proteins to Model DNA Vaccine Expression by Whole Animal In Vivo Imaging

PLOS One, June 2015

Vaccines are an incredibly potent tool in our arsenal to prevent infections. Simplistically they work by exposing the immune system to a safe part of the infectious bacteria or virus and evoking a memory response. When the vaccinated individual encounters the actual bug in real life, this memory allows the immune system to recognise and respond to the bug faster, thus preventing the infection before it takes hold. A critical step in vaccine development is the identification, isolation and mass production of the parts of the virus and bacteria that are able to evoke an immune memory. These components are often made up of proteins, which can be problematic and expensive to make to a standard that is acceptable for use as a medicine. Recently an alternative approach has been developed called DNA vaccination, which we describe in this review. DNA, the material of genes, contains the coding message for the production of proteins by cells. In the 1990’s a number of groups made the breakthrough observation, that if you inject DNA encoding proteins from a pathogen into a mouse, the mouse will make the protein in its cells and generate an immune response to this protein. This technique has the potential to significantly change vaccines because it is cheaper, easier and faster to make, for example, if a new viral epidemic occurs e.g. Ebola or MERS-CoV the time to make and test a DNA vaccine could be significantly shorter and therefore the spread of the disease would be reduced.

|

| The rainbow explosion of fluorescent proteins, From Roger Tsien's Nobel Prize Talk. |

However, DNA vaccines have performed poorly in early phase

clinical trials (i.e. they work really well in mice, but poorly in people). There

have been a number of reasons proposed for this failure, but one possibility is

that, after immunisation, the genes encoded by the DNA vaccine are not turned

into protein by the patient (technically referred to as poor expression). In our recent paper, we

set out to address this problem in our study, using a novel technology called

in vivo imaging, which uses the proteins that allow jellyfish to glow in the

dark and fireflies to flash at night. The original fluorescent protein was

green (named green fluoresecent protein), but since then a whole colour chart

of proteins has been developed with names like tdTomato and mPlum. If the

proteins are injected into mice, they can, using a special camera, be seen. The

colour of the protein has a significant impact on our ability to see it in

mice, blue and green proteins work poorly because the skin has evolved to

reflect light in these wavelengths as a defence against damage caused by UV

light. Red proteins tend to be better and in our recently published paper we

tested a range of red proteins delivered as DNA, called tdTomato, mCherry, mKatushka

and tdKatushka. We observed that only tdTomato gave us a strong enough signal

to see in the mice and that there are number of confounding problems with the

approach – pens we use to identify individual mice fluoresce in the same colour

as mouse poo.

|

| An Unusual Location for Scientific Training! |

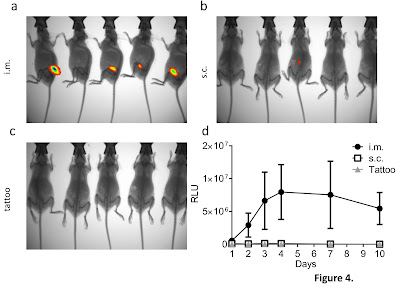

Delivering the DNA by different routes also had an impact on

the brightness with DNA injected into muscles producing a brighter signal than

DNA injected into the skin. We also looked into alternate methods of delivering

vaccines trying to more directly access cells involved in the immune response.

One approach we tried was tattooing, which is exactly as it sounds, we tattooed

DNA directly onto the skin of mice using the same system as you might get an

anchor or ex-girlfriend’s name tattooed on your arm. This came as a kit and to

get training, Katya (the lead author) had to get help from the local tattoo

parlour on Praed St! Delivering the DNA that expressed the red

proteins by tattoo failed to induce any signal, but when we used it to deliver

a vaccine, the mice were protected against influenza infection. However, this

result needs some caution as the equivalent body surface area in a person would

be the entire upper thigh!

|

| Visualising Luciferase transfection in vivo |

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council

(MRC) as part of a CASE studentship (collaborative awards in science and

engineering). These awards are a collaboration between academia and industry,

with the industrial partner providing a novel product or technology and

expertise in that area and the academic providing the capacity to perform in

depth, slightly more esoteric research. The scheme is mutually beneficial as

the academic partner gets a student to pursue novel areas and the industrial

partner gets to explore angles that would not necessarily fit within the usual

timeline constraints of getting products to market. We have been collaborating

with a biotech startup called Touchlight Genetics who have a novel

process for generating DNA without bacteria. As part of this collaboration, we

have previously shown that the DNA is as effective as conventional bacteriaderived DNA and we are working to develop new vaccines with the

technology. Overall, we conclude that imaging protein expression from DNA may

be useful for some applications, but is poorly predictive of vaccine efficacy.

Monday, 15 June 2015

#DistractinglySexy. Gender Bias in academia.

|

| Distractingly Sexy |

An incorrect assertion

“'Let me tell you about my trouble with girls.Three things happen when they are in the lab: you fall in love with them, they fall in love with you, and when you criticise them, they cry." Prof Tim Hunt (attrib).

The first I knew about this story was an email from my Dad saying to be careful of what you say and to whom and the trouble you can get yourself.

Sensible Advice.

That I will now ignore and blindly enter the minefield of writing about women in science as a man. I cannot fully appreciate all of the challenges associated facing women in the workplace and there are obviously better informed people than me who have done more reading and research on both the problems and the solutions. So why write this? Because the system is broken and we need to fix it, because I am inclined to value my own opinion and want to share it (one of the defining features of being an academic) and because I want to add my voice to people saying things need to change.

The fault in our stats

|

|

Figure 1. Staff at UK HE providers by occupation, age and

sex.

Taken from Staff in higher education 2013/14 (https://www.hesa.ac.uk/pr212)

|

Why do things have to be like this?

A question is why is there such an imbalance? In part it may reflect a historical bias, with the environment in the 1980’s and 1990’s being even less supportive than it is now. I had the privilege of knowing Prof Ita Askonas, who passed away a couple of years ago, a truly remarkable, supportive academic mentor, who rose to the top of her field in a generation when this was far from the norm, but she was one of a very small handful of female academics in her generation. There is some evidence of an upward trend – in 2004 only 21% of clinical academics were women, slowly rising to 26% in 2011 and 28% in 2013, with professorships at 11% in 2004 and at 17% in 2013 (medschools.ac.uk), but it is slow progress.

But historical bias is not the whole story and there are other factors. I would put children and childcare near the top of the list. There is still a perceived bias in expectation towards mums taking time off rather than dads. This is a whole complicated issue and which someone should address separately in a well rounded, but witty blog post . The MRC’s recent change to make fellowship eligibility independent of time post-PhD is a big positive step in this regards. There are some well described unconscious biases in recruitment, job advert writing, interviewing. There are self-reported biases in science by academics of both sexes (good nature op/ed article here). But the prevalence of gender stereotyping may unfortunately be propagating this bias. For example, Larry Summers (then President of Harvard) infamously commented on aptitude and gender (for fuller details see here) and a very brief dip into the interweb brings up, for example, an article about the coconut genomes from The Journal of Proteomics. An unlikely source of sexism, until you see the graphical abstract depicting a woman holding up two coconuts against her chest for no obvious reason (from http://www.stemwomen.net/recognising-sexism/).

I will re-iterate, opinions about the relative aptitudes of people based on what they are, are wrong. People make good (and terrible) scientists, regardless of race, sex, sexual orientation or background. It is also wrong to stereotype about lab personalities, for any given “but type X people are more likely to behave in Y way”, I can give you multiple examples of the opposite. These are wrong views and as trainers of the next generation (and parents of the one after that), we need to dispel them. At the end of the day, science – and the world that depends on scientific progress, needs the best qualified/most able people to deliver it.

It’s my laboratoire

The fact is that for multiple reasons it is harder to be a woman in science. Therefore things need to be done to level the playing field or we will not get the best people. However, it is easy to see why some people may not (consciously or subconsciously) want the status quo to change. Full disclosure: I am a white, privately educated, Oxbridge graduate, man. If 2 men are appointed to every 1 woman, then my chances are much improved. Any levelling of the playing field, could make the path harder for me and those like me. Whilst I assume my genius, social skills and zingy personality got me where I am, I have had every possible advantage from a loving home to extra golf lessons. There are some schemes and support networks, for example Athena Swan and awards targeted at women, or women coming back from childcare breaks but they are few and far between. Sadly, it is not uncommon to hear young male academics/ post docs/ PhD students complaining about how unfair these schemes that preferentially support women are. Interestingly these type of comments tend to tail off with age as these same young men see the problems their friends and loved ones go through juggling children and work. Optimistically, I think these complaints are a direct consequence of the terrible funding situation rather than the next generation of bigots being made. There is so little money available, that any factor that puts you at a perceived disadvantage seems outrageous. I do my best to point out the error of their ways, but it is a view point that needs to be changed. It probably doesn’t help that one of the schemes is sponsored by Loreal (brilliant Mitchell and Webb sketch on this).

We found love in a hopeless place

Was there any truth in the comment: "you fall in love with them, they fall in love with you". Yes, some people do fall in love in lab settings – I met my wife doing my PhD and many of my friends met their partners in science. But then again, many of my other friends met their partners in the army, being doctors, accountants, lawyers etc and then others met in bars, on Tinder, Grinder and Gap years in Africa. If you put people together, some of them will end up sleeping with each other.

Boys don’t Cry

Science is stressful, repetitive and mostly doesn’t work. PhD’s are more so, because you are learning and feel under a time pressure. Hindsight and experience are potent – of course I wouldn’t have done it that way, I would have included that control, I would have put the right chemicals in in the right order. Except when I am actually doing the labwork and adding my own unique cock ups to our long list of ways to fail at ELISA (we are currently at reason 20 – wrong species: long story/ different blog). Bosses are unsympathetic, under stress themselves and often just had a grant rejected. Even worse, Bosses also have a rose tinted view of how easy lab work was in their day, which with incomplete hindsight it possibly was, what was cutting edge to me is now provided in a kit to my students. All of this can add up to toxic interpersonal interactions. Some people cry, some people smash keyboards, things happen, to everyone. So again, an incomplete observation.

Amazing pithy conclusion

Amazing pithy conclusion

Sadly I don’t have one. There is a sex bias in academia (and many professions). It may (or may not) be improving. Changes need to be made, to make it fair so that selection is entirely on aptitude and ability, because science as a career is hard enough, without disadvantaging 50% of scientists. On the minus side there is still bias out there: on the plus side (some) people on twitter are provocatively funny (#Distractinglysexy), reminding us that the more we discuss workplace biases and educate the next generation the less likely it is to be perpetuated.

Post:Script Backlash against 140 characters

I have slightly amended this piece since I first posted it, due to the toxic backlash against Professor Hunt and the complexities of understanding what someone said when you only see a small snippet of it. I put this down to my naivety of social media and not truly understanding the impact it can have until I read Jon Ronson's brilliant - So you've been publicly shamed. The changes I made have left the sentiment intact (academia should be more fair), but in a less accusatory tone.Thursday, 21 May 2015

International travel, exotic locations, meeting new people. The cross we bear.

Interests: Travelling

|

|

The science park, Gdynia.

Not quite Croydon

|

After screening job applications, I began to wonder why so

many people have “interests: travel” on their CV to make them sound more unique

and thought? Oddly, no one ever puts interests: business travel, probably with

good reason. Business travel is really no fun, admittedly this is a massive

#middleclassproblem, but. Going somewhere “new and interesting” for work sounds

amazing, but when you arrive only to stay in an identi-kit business hotel in a science

park on the outskirts of somewhere that looks a little bit, but not quite like

Croydon, the shine goes off. My nadir experience was spending less than 24

hours in Gdynia (Poland), apparently the twin city of Gdansk, in the middle of

winter. Gdansk, so the guidebook tells me, is a beautiful example of eastern

European mediaeval architecture, Gdynia – less so. All I saw was the airport,

some rain, a Tesco, a science park, some snow falling whilst my taxi driver

drove at >10000000 miles an hour, Gdansk dock in the dark and the airport.

At least there are connecting flights from London (Luton), so I only had to

drive for another 2 hours to get home, rubbish.

Another day, another Novotel.

|

| 2 stand up guys in Bangkok |

One of the soul destroying features of business travel is the

decision by someone to make all business hotels look the same. Except the

shower controls, which are always different but have only 2 settings, too hot

or too cold. When the decision was made to make all hotel rooms look the same, did

they decide that two king sized beds was necessary and more worryingly, what

were they last used for? On one trip to Bangkok, a Thai friend with whom I did

my PhD escorted me round her home city. Turns out that to most people white man,

Thai woman means a different kind of escorting. When we got to the hotel I was

told very politely that ‘extra guests’ were not allowed. Now this was

mortifying on a whole number of levels. Firstly for my friend who is an

academic running her own lab and was horribly pigeonholed because of me,

secondly for myself for apparently looking like a western sex tourist but

finally for my night’s sleep and the hope that the sheets get well laundered if

this is a common problem. PS answers, she isn’t, I am not, they do. It’s not

only that these hotels are all the same, it’s also that they are all not home

and inevitably I have a sub standards night sleep, because it’s either too hot,

too cold, pillow’s too hard or not (even with the pillow menu), bed’s the wrong

shape, there’s a pea under the bottom mattress, I ate something with coffee in

sometime earlier in the week etc. On reflection I might be a fussy sleeper.

The king of rock and roll

| |

| Thanks Courtney, that looks lovely pet |

I could go on about the enumerate, ungrateful petty problems

I have when I am travelling, But this has all taken a slightly unfunny, Michael

Macintyre-stating the bleeding obvious-it’s funny coz its true riff. Instead, I

will admit a lot of my whinging is for ‘comic’ effect – and because I like the

sound of my own voice, even on paper. There are, to be honest, a number of

positives about travelling with work. The biggest one is that you get to

pretend you are a Rockstar, admittedly not a huge cocaine snorting, 18 girl

orgy, room trashing, TV out the window, rolls Royce in the swimming pool, Keith

Richards/Keith Moon/Axel Rose/Tommy Lee Rockstar. To be honest it’s a bit

closer to being James Blunt, but he’s still a Rockstar (and does have an

awesome Twitter response history). Leaving clothes on the floor, not making the

bed, leaving the lid of the toothpaste tube and coming back to find the room

immaculate, amazing. It is just possible that my aspirational Rockstar status

is a bit adrift from reality, but I bet Kurt Cobain never put the lid on the

toothpaste – that’s probably why Courtney Love shot him. Like I said, not

superstar stuff, but still quite a treat, especially when you spend most of

your time clearing up after wayward children and PhD students. Having low

expectations helps.

How to win at travel

Asides from the low budget Rockstar fantasies, there are a

number of things that do make life on the road endurable:

Skype (other free video conferencing software is available)

One of the toughest things is being away from your family.

In the not so distant past, staying in touch would have meant acquiring

handfuls of small change, then standing in some freezing, piss filled phone

booth or paying exorbitant hotel dial out rates. Now with the ubiquity of smart

phones and Wi-Fi you can video link into the heart of the home at the most

inconvenient times – bath time is best – to remind yourself of the chaos you

have left behind at home and that being away from it for a few days is probably

not so bad.

The Euro

I am not entirely clear about the economic arguments, but

having one currency for every country I go to is amazing. It means having a

wallet preloaded with some kind of monopoly money which you can use for every

trip. Until you go somewhere in Europe which isn’t in the EU. (NB John’s travel

tip – they use Krone in Iceland)

Running

One way in which I differentiate between different places is

to go for a run. Again t ’internet is a Godsend as with the help of mapping

apps you can find a reasonably decent run. Normally around some of the finer

turn of the century soviet era light industrial estate in the rain, but at

least you see something to indicate you’ve left home.

Being fussy

One thing I only recently discovered is that you are the

customer. If you are from outside England, this is probably not a revelation,

but to us it is mind blowing. Rather than meekly putting up with a pokey garret

next to the lift with a broken toilet, I have started asking for a quiet room

at the outset and if it is no good going back and asking for another one. This

has considerably upped the quality of the experience.

Amazing things sometimes happen

Swimming in a glacial melt river in Iceland that has been

heated by volcanic run off to bath hot temperature whilst being paid by the EU.

If every member of UKIP got to do this I think they’d soon change their tune.

Swimming in a glacial melt river in Iceland that has been

heated by volcanic run off to bath hot temperature whilst being paid by the EU.

If every member of UKIP got to do this I think they’d soon change their tune.Beer

Drinking Belgian beer with Danes

at 2 in the morning… what could go wrong?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)